In the history of video gaming, Atari's Breakout is arguably second only to Pong - the Atari title that preceded and influenced it. And for such a basic game, the story of its creation is genuinely surprising, featuring as it does star appearances from some of the biggest names in technology. Think of the most famous tech guy ever. Yes, him. No, not the one with the bowl-cut. No, not the teen nerd. The other one. And his mate.

WHAT IS THIS BREAKOUT ANYWAY?

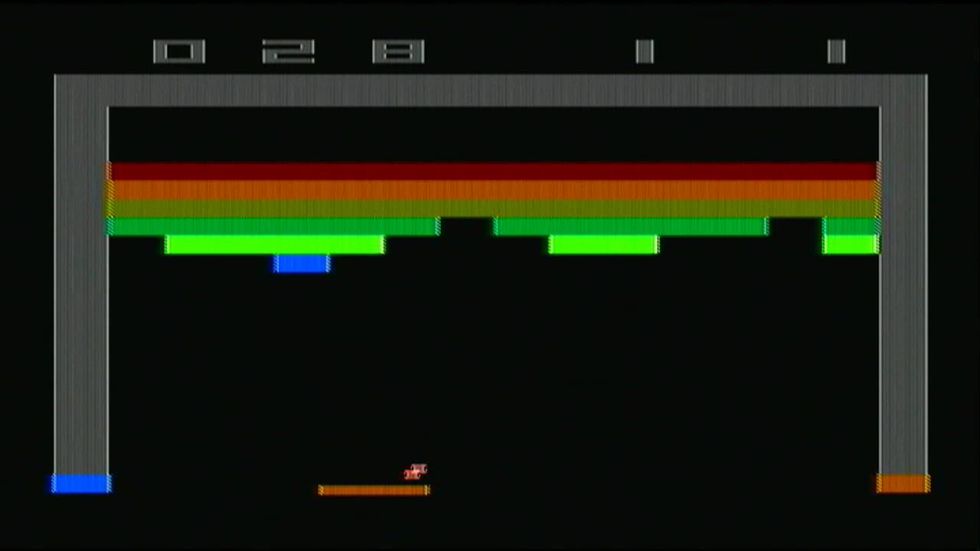

Released at a time before gaming had made the transition from arcades to the home, the 1976 classic took the multiplayer mechanic of Pong and adapted it for solo play - you used your block-shaped paddle to deflect a very square-looking ball onto a wall of blocks, with the ultimate aim being their complete removal.

Want to play it right now, on your desktop? Here it is.

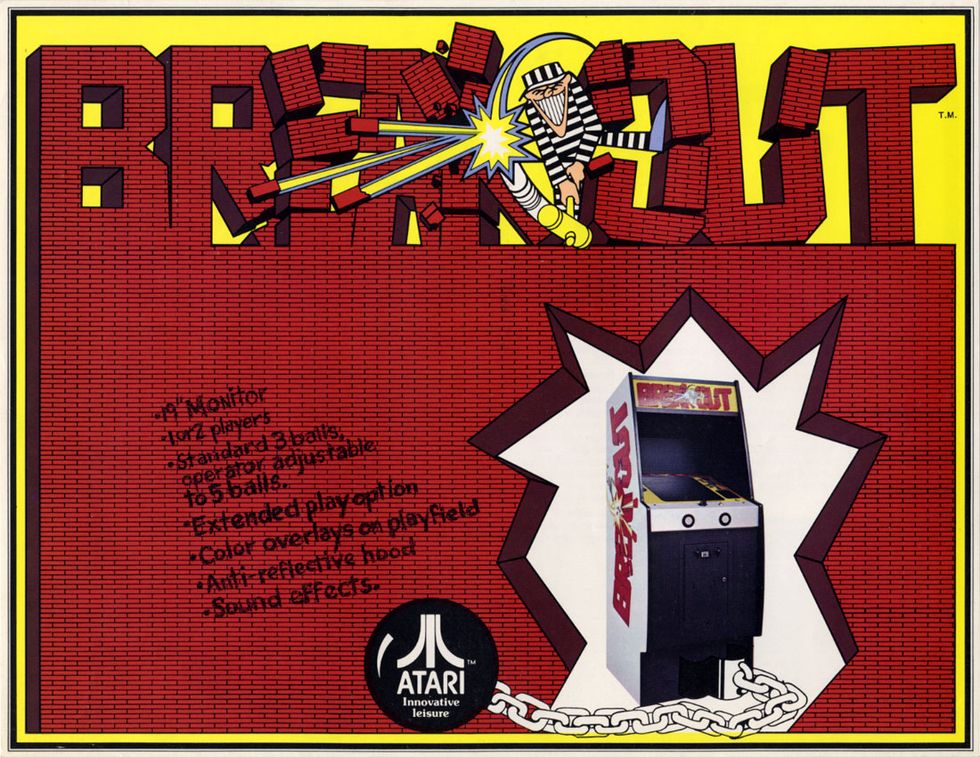

Back in the mid-'70s, Atari's business was booming thanks to the incredible success of its Pong arcade cabinet. However, Atari founder Nolan Bushnell - often credited as the man who brought video gaming to the masses - was keenly aware that Pong had started a gold rush, and rival companies were attempting to muscle in on his company's territory. He knew that if Atari was going to remain the industry leader it needed to craft new and addictive games which could achieve the same popularity as Pong and keep players hooked.

However, he obviously didn't stray too far from the Pong template, as his vision for a single-player version of the game - which would become Breakout - retained the same "paddle and ball" mechanics.

BREAKING THE MOULD

Bushnell conceptualised the game with the assistance of Steve Bristow, and knew deep down that it was going to be a smash hit. However, as a businessman he had one eye on the bottom line, and was keen to ensure that Breakout would be as cheap as possible to manufacture.

Games of that period used dedicated logic chips rather than microprocessors, with a typical game needing around 150 to 175 chips. With each title shipping around 10,000 units, Atari could potentially save around $100,000 for each chip that was removed from a game's design.

To achieve his goal of removing as many chips as possible from Breakout's design, Bushnell told his engineers that he would give a bonus to anyone who could prototype the title with fewer than 75 chips. For each chip removed from the design, he would pay a bonus.

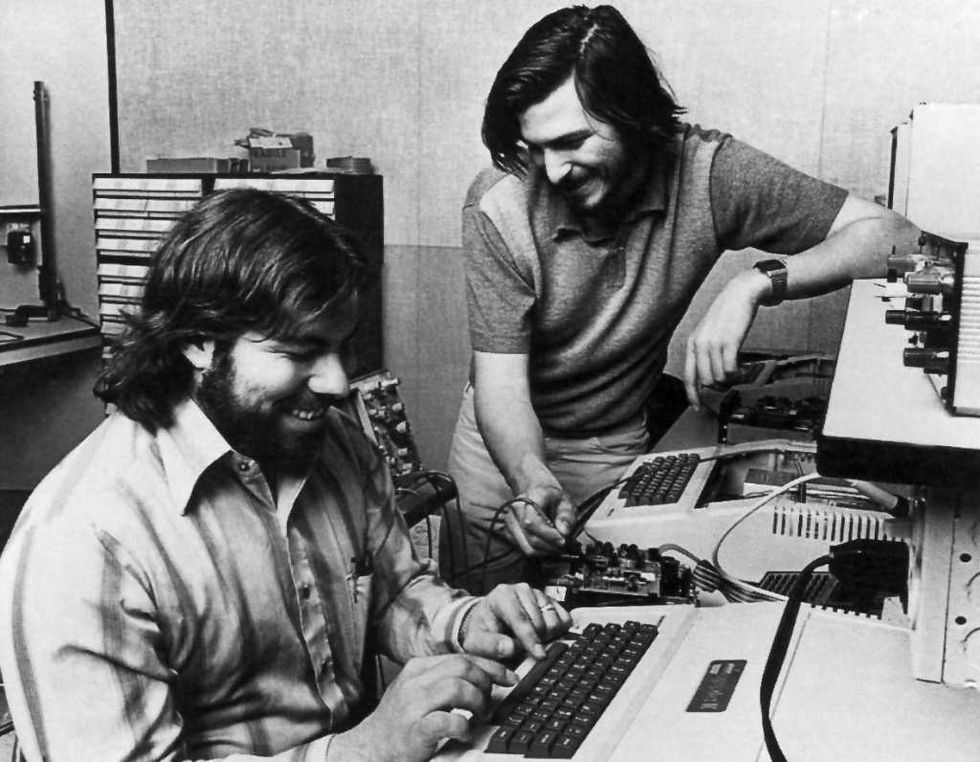

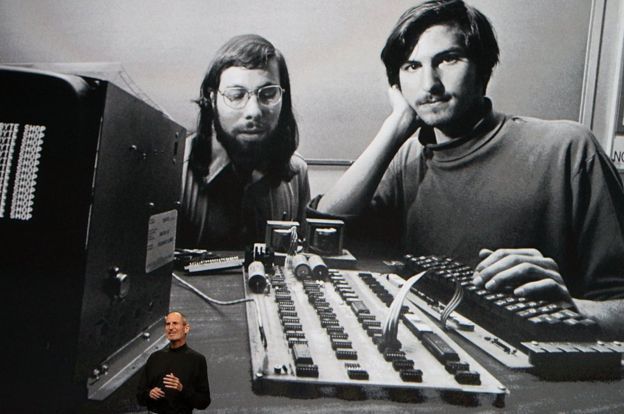

The man who stepped up to the plate was none other than Steve Jobs.

Atari was one of the late tech legend's first... well, jobs, and he enthusiastically informed his boss that he could make Breakout a tighter game from a production standpoint and would supply a prototype in four days. However, in typical Jobs fashion, he was writing cheques that he couldn't cash. Instead, he planned to enlist the assistance of his close chum and tech wizard Steve Wozniak (OH HAI WOZ) to do the dirty work. Jobs promised to split the bonus with his friend.

ENTER THE WOZ

Wozniak - who was employed at Hewlett Packard at the time - was keen on creating hardware and was considered to be one of the most brilliant members of the "Homebrew Computer Club", an local organisation devoted to tinkering around with computer systems.

Woz (as he was affectionately known) would visit Atari during the evenings and spent around 72 hours minimising the circuitry for Breakout. According to former Atari staffer and Pong designer Al Alcorn, Wozniak whittled the design down to around "20 to 30 integrated circuits" - a truly amazing feat for the time. However, the final physical prototype submitted to Atari had 44 chips, which was still an achievement when you consider Bushnell's original challenge.

Atari paid Jobs $5,000, but he kept this secret from Wozniak and only paid him $375. Wozniak believed for years afterwards that Jobs had only been paid $750 by Bushnell, and when he eventually found out, it clearly had a long-term effect on their friendship.

"I knew he believed that it was fine to buy something for $60 and sell it for $6,000 if you could do it," Wozniak told Steve L Kent in The Ultimate History of Video Games. "I just didn't think he would do it to his best friend."

Jobs said that he invested the cash into founding Apple, the company which would make both his and Wozniak's fortunes, so you could say that his deception was for their mutual benefit rather than his own personal gain, but the fib clearly rankled the otherwise affable Woz.

The irony of this fascinating saga is that when Wozniak's ingenious prototype was delivered to Atari, the company found it impossible to replicate it on a mass production level. The design was too tight and compact for Atari's engineers and production process to deal with, and in the end the final Breakout board shipped with around 100 chips - although Wozniak states that in terms of gameplay, it was identical to his version.

AND IT DOESN'T END THERE

Working on Breakout gave Wozniak the inspiration he needed for the Apple II, one of the most influential personal computers ever made. He included features such as paddle support for games and even made his own Breakout clone for the system. However, Breakout became a significant commercial success in its own right, and was duly ported to Atari's best-selling VCS home console as well as a wide range of other systems.

Conversions of the classic title are still appearing today - here it is again in case you missed it above - while numerous clones have risen up over the years, including Taito's Arkanoid, Namco's Quester, Nintendo's Alleyway and more recently Popcap's Peggle.

When you think about it, it's truly incredible that one of the gaming industry's first titles is still influencing the games that we play 40 years later. And it's perhaps even more striking that despite its age, Breakout remains an addictive experience; proof positive of Bushnell's Law:

"All the best games are easy to learn and difficult to master."